Will it really be a "long winter" for Europe?

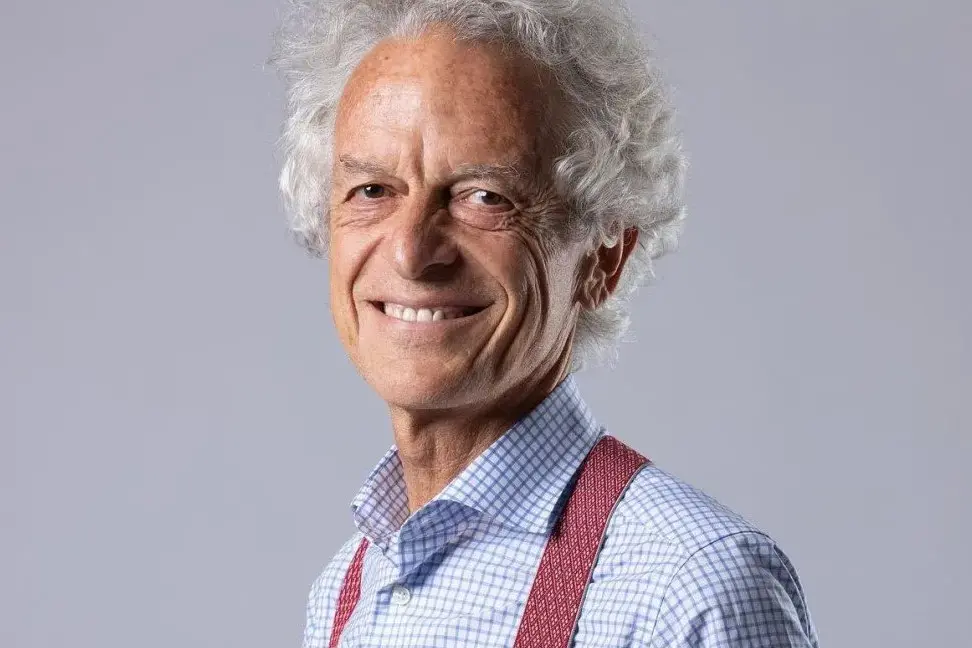

Federico Rampini in his latest book helps to navigate between real crises and false Apocalypses of our timePer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

Wars and energy shortages. Climate change, new migrations and demographic crisis. Raw materials and food to grab before others do. Are these the dynamics that, like it or not, we should get used to? Have we truly entered an era of scarcity – of energy, health, safety – or is it a temporary phenomenon that we will emerge from as we healed from other crises? Is the trauma, which began with the pandemic and aggravated by the war in Ukraine, just the beginning of a historical phase marked by hardships, sacrifices, rationing and cuts on everything?

Federico Rampini offers us his point of view in the recent "The long winter" (Mondadori, 2022, pp. 240), an essay that tries to analyze the dynamics of our time without being crushed by contingency, but trying to reflect on events and processes in the light of our history.

So we ask Federico Rampini to explain to us what he means in his book when he speaks of the "era of scarcity" for the time we are living in:

“We feel besieged by all sorts of shortages. There is a lack of energy and in some areas of the world even water. Essential goods cost more. Too many companies complain about not finding workers. In the background there is the decline of the population that does not spare China. With inflation and interest rate hikes, money becomes rarer and more expensive. Energy seems like a recent emergency, in reality the crisis comes from many years of bad decisions. Putin gave the final push to a building ready to collapse. Europe boasted of taking big steps towards a very clean future, all based on renewable energies, without seeing what it was really doing. The money shortage still leads us back to the fateful 1970s. By consuming less, by reducing demand, another kind of scarcity occurs: it is the recession in our spending. This too is fabricated shortage: by central bank intervention which erases 14 years of abundant money».

But have we really entered an era dominated by scarcity, an age really worse than those that preceded it?

«From the (completely erroneous) prophecy on the end of development that was the obsession of the seventies, a doubt should have crept among us: that seeing the imminent Apocalypse around the corner is a trait of decadent civilizations. Back in the 1970s, one of the reasons why we were wrong in predicting the end of development was the underestimation of the market economy. A few years after the publication of the Club of Rome's report on The Limits to Growth in 1972, the greatest development in human history took off, that of China and India, which saved two billion people from poverty. And yet, the apocalyptics continue undaunted and unpunished, they never criticize the past and present us with new catastrophic scenarios. Instead, the dynamics of supply and demand continue to be a powerful force for change. Shortages lead us to correct the shot, to fix imbalances, to experiment, to explore new paths. The electric car and photovoltaic panels would not have been born without the stimulus to innovate that came from the high price of petrol and the 'Sunday walk' of fifty years ago».

In this moment of difficulty, is it right to invoke the greater presence of the state or can it be harmful?

«In Europe, various public opinions are increasingly asking for a state. The aid provided during the pandemic has been a starter for all that is required of governments to protect us from adversity. A mother-state that is too intrusive numbs vital reflexes and is not efficient: it was precisely the choices of governments in the past years that fabricated this disaster. Italy is the western country most vulnerable to the statist temptation, due to its already excessive public debt; because it has an intrusive and inept bureaucracy; because a part of its population has introjected welfarism as a horizon of life».

Who has the best "weapons" to get out of the current period of crisis? America? China or Europe?

«The passages of the era, the great historical ruptures, can be understood by looking at a fundamental triangle: energy, currency, technology (which includes weapons). America still dominates that strategic triangle. It is the only superpower to have energy self-sufficiency, a universal currency and, for now, also technological superiority. We can add a positive demography, which distinguishes America from China and Europe. China has handicaps that it tries to overcome, for example by gaining a monopoly on green technologies (solar panels, electric batteries) thanks to Western ingenuity. Europe is lagging behind. His ideas are confused, entangled in dogmas and taboos. He has more ambitions than ambitions. It has easy disarmament. And with disarmament comes submission. The long winter marked by so many scarcities is also the winter of reason».

But how do we get out not so much of the crisis, but of this sense of impending apocalypse that seems to have gripped the West?

“We will overcome it if we draw on the qualities of our role model, not if we admire our haters. The long winter can herald a season of creativity, in which we will find innovative answers to our energy and economic problems. But we must free ourselves from a habit, from a fashion that dominates the discourse of the media and the elites: the habit of describing the world on the brink of the abyss, one step away from environmental disaster, from mass hunger, from uncontrollable migrations. To begin with, let's study history and science. Many of the current alarmisms are the remake of false prophecies that made proselytes in the past centuries. A scientific approach to climate change advises us to act to slow it down as far as possible, but also to mitigate its effects and protect ourselves. As for the aggressive imperialisms of powers such as Russia and China, Turkey and Iran, one must open one's eyes and practice the saying of the ancient Romans: si vis pacem, para bellum. If we want peace, we must invest in security".