Thus books change life

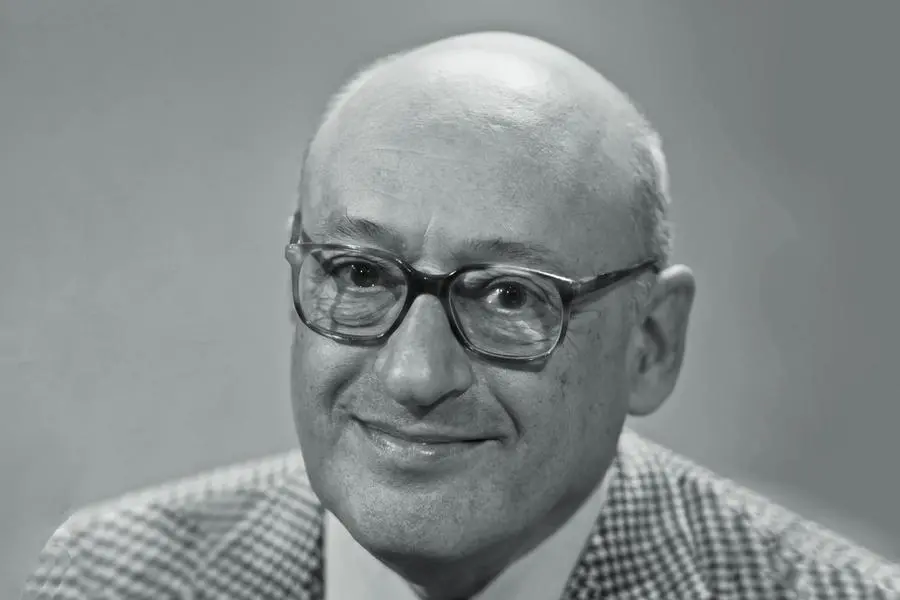

The critic Piero Dorfles and the best work there is: reading

Per restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

Marco Tullio Cicero, more than two thousand years ago, wrote that a house without books is like a body without a soul and a room without windows. St. Ignatius of Loyola compared it to a fortress without weapons: easy to conquer because it was defenseless. Having read these maxims, one then wonders if some of the problems that have afflicted our country since time immemorial - as well as a certain apathy of us Italians in dealing with them - are not also the result of a certain propensity to avoid reading, indeed the fatigue of light. In fact, Italy is certainly not a country of readers.

This is certified by the data of the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) which speak of 69% of Italians who have a reading competence below the minimum level to understand a simple text. This bad result is certainly linked to the dynamics of modern communication, which imposes immediate and short communication codes. But there is something more as well identified by the critic Piero Dorfles in his recent “The work of the reader” (Bompiani, 2021, pp. 252, also e-book). In fact, there is a widespread tendency to emphasize the pleasures of reading in a rhetorical and emphatic way, while it is not taught, however, especially to younger people, that reading is a chore. It takes effort, it needs time, solitude, application. It requires constant training so as not to lose practice.

It then becomes even more complicated to make it clear that this effort will then be rewarded by the encounter with the extraordinary world that literature makes available to readers. The goal is too far for newbies to the written page, too hazy. Perhaps the expression "reading is a pleasure" has been overused and forgotten to say that reading first is useful.

As Dorfles says at the opening of his book because in everyday life those who do not read books seem to get by very well, one would think that the inability to read has little to do with the ability to be good citizens, competent workers, respectful and empathetic people. The reality, however, is that those who do not read will hardly find elsewhere what the reader finds in books. In the books there is the history of man, with his conquests and failures; there we are, with our feelings, dreams, actions; there is that symbolic experience that pushes us to develop ingenuity, fantasy and imagination. Books, Dorfles explains well, are one of the most extraordinary resources to save us from the trials of life: those who can read do so even in the face of the most dramatic anxieties, the deepest anxieties, the most exacerbating pains.

Going also on the practical side and always referring to the new generations - those who seem the least inclined to traditional reading - the children will find themselves, in fact, in a thousand situations in which they will have to use words and even more in which they will have to understand a text that they have front. Maybe simply for a competition announcement. And if words make them difficult, they will suffer the words of others. Therefore they will not be able to defend themselves, to have their say, to assert themselves. The first step must be this: recover the practical reason for reading and the drive to keep in training by reading everything and everything. Readers and even citizens become like this, not shunning fatigue and not looking for shortcuts.

Piero Dorfles also offers us some suggestions in our path as readers. It illuminates the perspectives that literature can open to us by collecting some classic works grouped by major themes: the fundamental ones of human experience. Thus we find in the book described novels that deal with the central theme of modern man's ineptitude, such as the works of Italo Svevo and Cervantes' Don Quixote. And again those works that better than any essay know how to tell us the tragic charm of war such as "A year on the plateau" by Lussu or "The sergeant in the snow" by Mario Rigoni Stern.

We then find, in "The work of the reader", the judgments on the works cited, a rare pearl in an age in which no one is criticized anymore. No slating, however, taken positions, well argued with which Dorfles helps us to reflect - but it is only an example - on why books that Dorfles defines with a beautiful synthesis inherited from the novel "A Clockwork Orange" "mielestrazio" (sweetish to the point of becoming a real torment), such as "The Little Prince" or "Little Women", are however masterpieces and have millions of fans around the world.

In short, "The reader's work" is an interesting and very personal survey of the universe of reading, a small and well-stocked library that helps us understand, as the author writes at the end, that "books and reading do not bring certainties, but doubts. Not happiness, but knowledge. They don't explain the why of life, but they stimulate questions and self-awareness. They cannot overcome the difficulty of finding meaning in our being, but they allow us to remove the risk of getting lost in nothingness and force us to place ourselves at the center of all life. To ask ourselves precisely why we are here today. That's why the reader's work is the most beautiful there is ".