This is how the press changed the world

In Rosa Salzberg's book a little-known aspect of a revolution that shaped our civilizationPer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

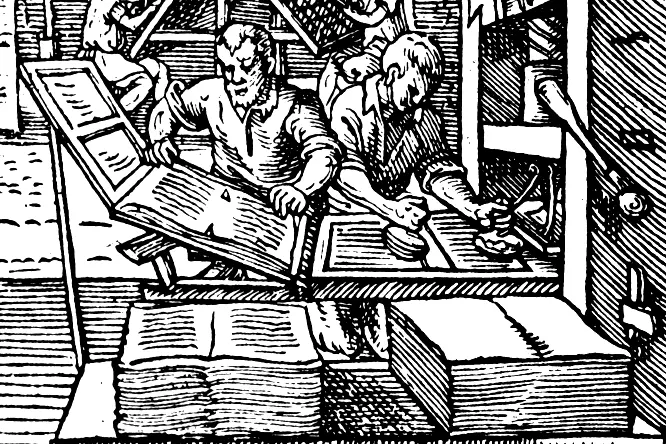

Until the birth of printing, books were written by hand, one at a time, by scribe monks, who took years to complete their work. Everything changed with the introduction of the printed book. To understand the innovative scope of movable type printing, we can compare it to e-mail, which has revolutionized the way we communicate. A click on "send" and that's it, I can send my message to one or many people practically in real time. Similarly, Johannes Gutenberg's famous invention of 1454-55 definitively changed the way ideas were spread, facilitating the publication of numerous works and writings of various kinds. With movable characters, reusable several times and joined to form words, lines and pages, books and texts could be printed in series, in dozens and dozens of copies: knowledge thus became "faster".

When we think about the introduction of the first printed books, however, we focus almost exclusively on the volumes dedicated to "high" culture: the Bibles printed by Gutenberg, the refined editions of Aldus Manutius in Venice. Rosa Salzberg , professor of modern history at the University of Trento, in her " The city of paper " (Officina Libraria, 2023, pp. 280) tells us about some lesser-known aspects of the revolution linked to the press.

A narrative that is the result of long historical research and which starts in the first pages of the book from a minor story. In the summer of 1545, in Venice, an itinerant singer named Francesco Faentino set up his wooden stall perhaps near the Rialto market or near Piazza San Marco and began selling a printed booklet with a scurrilous and Boccaccio-esque subject. People rushed to buy the booklet, but such enthusiasm did not involve the Venetian authorities who threw Faentino in prison on charges of blasphemy. Our singer got away with a hefty fine, but the story opens a glimpse into how popular and ephemeral printed production already existed in the sixteenth century, capable of intercepting the varied tastes of the population of the time. This episode and others recounted in the volume, in contrast with the traditional image of Venice as "la Serenissima", calm and orderly, evoke the noisy, changing and transitory life of the city at street level and offers the first view from below of a of its most productive and creative industries.

The outcome is a new and unexpected perspective on Renaissance culture , characterized by fluid mobility and a dynamic interweaving of texts, ideas, goods and people. The book follows the flow of ephemeral prints (pamphlets, operettas and broadsheets) that poured from Venetian presses starting from the end of the 15th century. These were the most visible and accessible products of the printing house, often sold on the streets and declaimed by street entertainers. Closely intertwined with oral culture, these texts contributed to the creation of new audiences, providing information and entertainment to diverse audiences and transforming the city into an epicenter of vernacular literature and performance. Examining the ways in which the production and dissemination of low-cost printing infiltrated the Venetian urban fabric and changed the course of the city's cultural life, the book also analyzes how local authorities sought to regulate these flows by intensifying censorship. and control during the 16th century. In short, the volume shows us how news and ideas, initially known to a few and contained in convents and places of power, spread to wider segments of the population, causing, albeit gradually, a progressive increase in the level of education.

A process also facilitated by the printing of texts no longer only in Latin, but also in the vernacular, an ephemeral, popular, Boccaccio-like, but extremely vital production which is at the center of La città di carta.