Can it happen again?

Historian Laurence Rees takes us on a disturbing journey into the Nazi mindsetPer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

There's much talk these days of a crisis in democracy, of a return to an authoritarianism and personalization of politics that seemed to belong to the twentieth-century past. We're witnessing a resurgence of anti-Semitism and neo-Nazi movements with groups inspired by Hitlerian ideology, even present in the parliaments of European nations, as is the case in Greece and Germany.

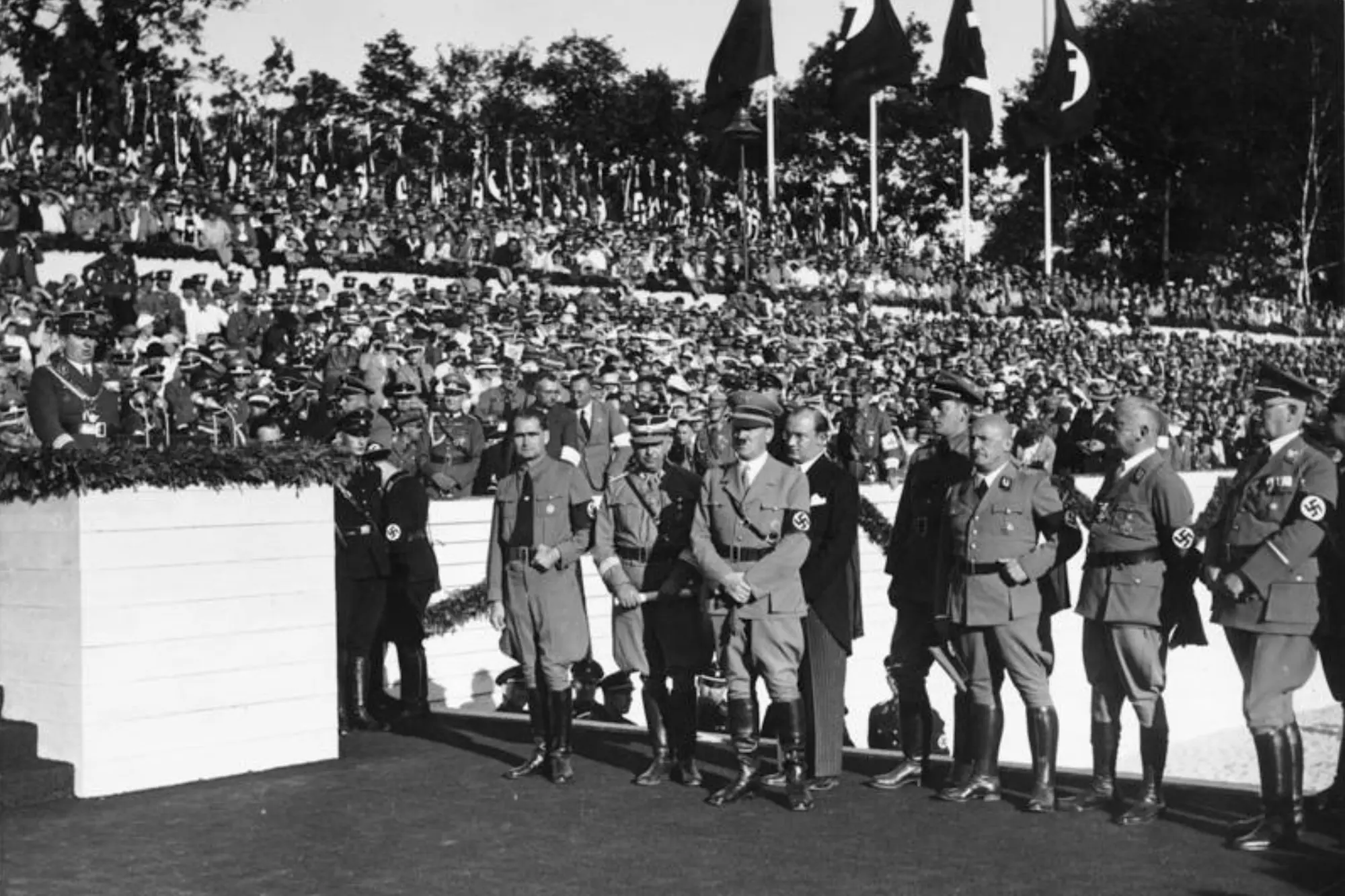

In short, the ancients said that history is a teacher of life, but given the way things are going, it's doubtful whether we can learn from the mistakes and horrors of the past. This doesn't mean we shouldn't try to help, especially the younger generations, those most exposed to the myths of force and oppression, fully understand the Nazi ideology. Faced with the aberrations committed by the Nazis before and during the Second World War, several questions have always arisen, almost automatically. First, we wonder how one man, Adolf Hitler, could dominate the minds and consciences of tens of millions of Germans. The second concerns how it was possible for a political movement to emerge whose sole raison d'être was hatred taken to its extreme consequences.

In his essay The Nazi Mind (Bompiani, 2025, pp. 512, also available as an ebook), Laurence Rees , one of the world's leading experts on the Second World War, explores these and other questions related to the Nazi era from an original perspective that lucidly blends history and cutting-edge psychology. Using these tools, he offers us an in-depth, revealing investigation that attempts to answer the most distressing and timely question of all: could it happen again? Or rather, is it already happening somewhere, and why? Through previously unpublished testimonies of former Nazis and citizens who grew up in the heart of the Third Reich, Rees leads us on a disturbing and necessary journey into the mindset of those who permitted, accepted, or justified evil. And he offers us twelve warnings, twelve warning signs to watch for today, in our leaders, in our societies, even in the places we think are immune: democracies, the lands of the free, those in which it seems unthinkable to find the seeds of a dark evil. What are these warning signs?

Some are immediately recognizable in our time, such as stoking fear, exploiting faith, exacerbating racism, undermining human rights, encouraging the spread of conspiracy theories, and identifying with the idea that debate must always center on a clear and irreconcilable opposition between the parties. Other warnings concern more subtle behaviors, aimed at exalting the "leader," the leader, the Führer of the moment. These are actions such as corrupting youth, extolling the heroism of those in command, resorting to violence without getting one's hands dirty, and seeking the support of the powerful and the self-righteous. For Rees, these and others are alarm bells, because The Nazi Mind shows that the most atrocious crime of the twentieth century is not just a historical fact, but a dark mirror in which the present risks being reflected. Rees's book is, in fact, a reading that challenges us as witnesses and protagonists of historical events. And it can become a guide to not turning away when the mindset of horror prevails over human values, reminding us that Hitler's words took root in the consciences of one of the most cultured peoples of modern Europe. In short, a true reminder of how ludicrous the line is between civilization and barbarism, between Eden and hell, between refinement and primordiality.