Victor Hugo, Ventotene and a Passport for Sardinia: History of a Possible Europe

In a letter dated 1870 and addressed to the Sardinian archaeologist Tamponi, the story of a "noble land", with a place already written in a civil, free and just futurePer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

At a time when the Ventotene Manifesto returns to the center of the Italian debate, celebrated, reread, sometimes contested , it is perhaps worth comparing it to a lesser, but no less revealing, story . A story that almost by mistake passes through Sardinia , touches the hands of Victor Hugo , and gives us a different idea, more poetic but also more human, of the Europe that could have been .

In June 1870 , a few days after France declared war on Prussia, Victor Hugo was still in exile in Guernsey. From afar, he watched the world hurtle toward a new conflict, and with the lucidity of a poet and visionary, he wrote a reflection in his notebooks that today seems incredibly relevant: “C'est le rêve des États-Unis d'Europe”, “it is the dream of the United States of Europe”.

It was not the first time he had used that expression. Hugo had already evoked, in speeches and public texts, the dream of a European federation founded not on force, but on brotherhood between peoples . But in those days, the idea took on an even more precise, almost geographical, form.

In a little-known letter, written on June 29, 1870 and addressed to the Sardinian archaeologist Pietro Tamponi, Hugo states with extraordinary simplicity that even “la Sardaigne y aura sa place.” Sardinia, too, will have its place.

The letter, now preserved at the University Library of Cagliari, is one of the most surprising and sincere testimonies of Hugo's European thought . It is not a public declaration, nor a political proclamation. It is a personal, heartfelt response, full of gratitude and idealism. Hugo describes Sardinia as a "noble land", inhabited by "noble sons" , and directly connects that peripheral region to the common destiny of a Europe that is finally civil, free, and just . The tone is not rhetorical, but vibrant. One can perceive in filigree the urgency of a dream that seeks a form.

And thanks to the careful and rigorous work of researcher Liano Petroni, who studied and published this correspondence in an academic article of extraordinary clarity, today we can reconstruct with precision the contours and meaning of this epistolary exchange. Petroni has investigated its historical context, symbolic implications and possible connections between Hugo, Italy, and the Risorgimento.

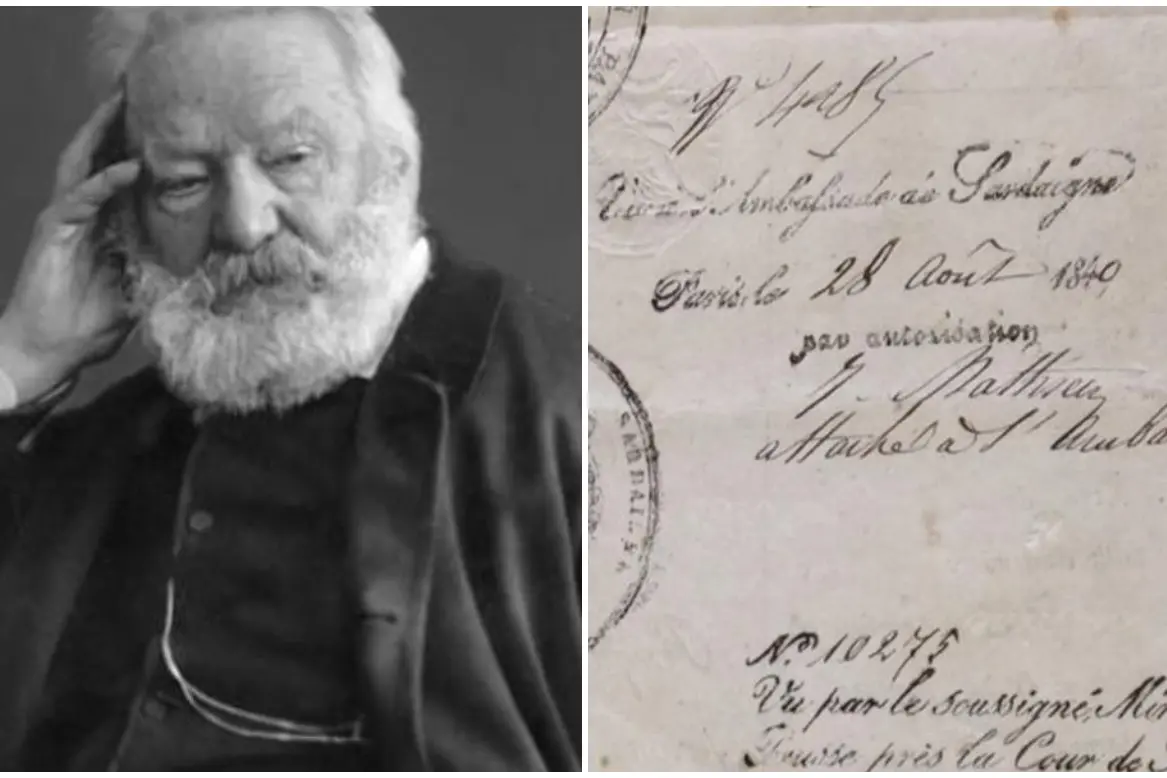

And perhaps it is no coincidence that Hugo chose an archaeologist as his interlocutor . Tamponi, a mostly forgotten figure, lived near Caprera, near Giuseppe Garibaldi — with whom Hugo maintained an epistolary relationship of mutual admiration. In Tamponi, perhaps, Hugo saw the Italy of the Risorgimento : not that of political proclamations, but that of silent dignity and culture as an instrument of liberation . But the story does not end there. Indeed, it takes on an even more fascinating twist. In July 2023, while leafing through the catalog of a Parisian auction of Drouot, I came across a surprising document: an official passport issued to Victor Hugo in 1840 to travel precisely to Sardinia. The document bears all the correct stamps, is signed, and stamped by the embassy of the Kingdom of Sardinia in Paris. On August 28, Hugo obtains the visa. But the next day, August 29, he left instead for Germany, along the Rhine. There he collected materials for a work that would become Le Rhin, published two years later.

The trip to Sardinia, therefore, does not happen. But everything remains: the intention, the documentation, the project. Why did Hugo want to go to Sardinia? Some clues suggest that it was not a simple tourist whim. Hugo had already decided to work on a new poetic volume, perhaps a hybrid between a travel diary, historical reflection and interior landscape - as he will do for the Rhine. He had prepared himself, he had asked for the visa well in advance. But for a practical reason - supposedly a delay in the delivery of the document - the trip is postponed, and Sardinia remains off the route. In its place, there are the cows of the Rhine, as he himself notes with disappointment in his notebooks. But the idea was there. And perhaps it never completely went away.

Thus, in 1870, thirty years later, Sardinia returns to his thoughts, no longer as a physical destination but as an ideal place. Hugo does not need to have been there: in his vision, Sardinia is already part of the future Europe. A place that has fought, that has memory, that has dignity. An island that can — and must — have its place in the United States of Europe. It is not just poetic generosity. It is political intuition. It is the ability to see, in a peripheral detail, the reflection of a larger civilization.

In our present, in which the idea of Europe seems to oscillate between technocratic coldness and tired utopias, it is worth recovering this forgotten page. Victor Hugo was not a federalist in the modern sense, nor a professional politician . But he knew how to imagine a Europe that was not only a market, but a moral community . And he did so with the language he knew best: poetry, letters, symbolic gestures.

Even an unused passport can say a lot, centuries later. The coincidence is almost too perfect: a document signed by Hugo, with “destination: Sardaigne” written on it , and a letter in which he writes that Sardinia will have its place in the European project. They seem like the two halves of a promise never fulfilled. We have long celebrated the political part — the Ventotene Manifesto. Perhaps it is time to rediscover the poetic part too: the one made of impulses, travel errors, wrong addresses, unpublished letters. It is there, in those shadowy areas, that the truest part of Europe sometimes hides.

And after all, what is the European Union, if not an enormous correspondence between islands that are still looking for each other? Victor Hugo never arrived in Sardinia. But today, thanks to a letter and a passport kept almost by mistake, we can say that Sardinia - at least in his thoughts - did indeed arrive. And perhaps this is the most ironic and precious lesson of all: that an idea may not even set foot on land, and yet leave an indelible mark. All it takes is a stamp. And a dream with the right address.

Simone Falanca – Scholar and writer