The Table of the Powerful: Food, Luxury, and Power in Renaissance Courts

In Jean-Claude Vigueur's essay, "At the Table with the Lords", an in-depth look at how the consumption of certain foods and the sumptuous setting have long determined the perception of princes and rulersPer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

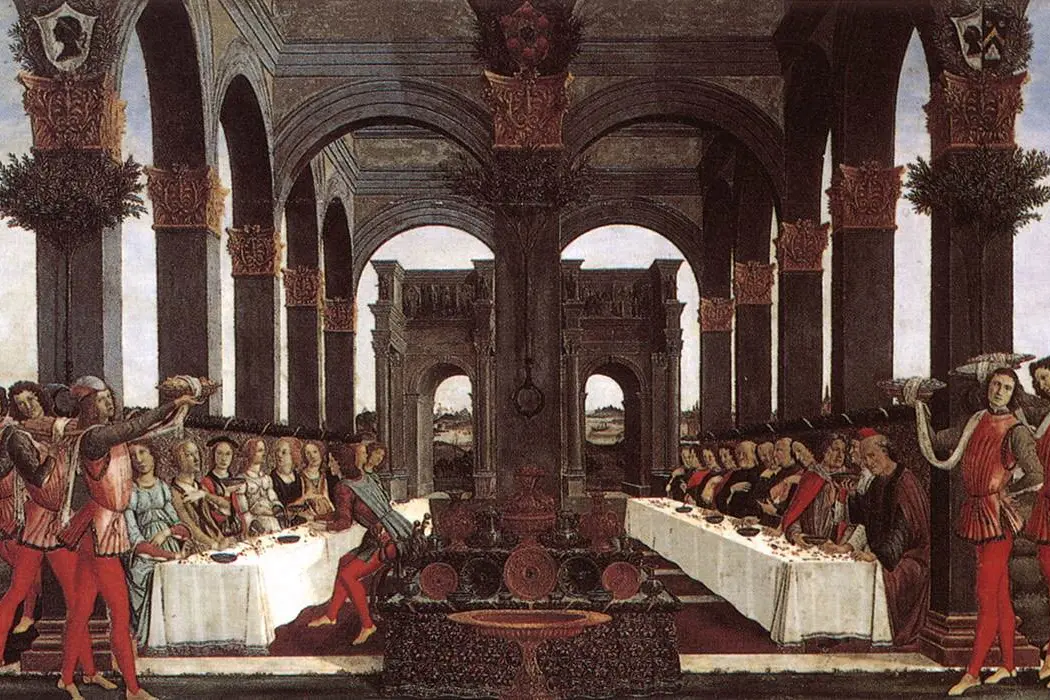

Not just culinary art, but also scenography, politics, and diplomacy: this was a banquet in the heart of the sumptuous Renaissance courts. Not simply a moment of gastronomic pleasure, but a true theater of power. It was a stage where the lord and prince stood as the undisputed protagonist, surrounded by his entire court, who simultaneously paid homage and helped demonstrate the greatness of their host to the world. The lavishly laid tables became showcases of magnificence, where every dish recounted an alliance, every gesture of service was a choreography aimed at captivating the audience, every spectacular interlude could deploy, disguised with the exquisite art of worldly seduction, brutal political strategies and a ruthless desire for domination.

This universe, seemingly so far removed from our sensibilities—but don't the powerful still try to impress their guests and the "people"!?—is the focus of Jean-Claude Vigueur 's latest essay, one of the greatest experts on the political history of the Italian Middle Ages and Renaissance. In his book, " A tavola con i signori" (Il Mulino, 2025, €36.00, 300 pages), Vigueur reminds us that the Renaissance was an age of artists and men of letters, but also of lords and princes who ruled the roost and certainly didn't like to mingle with the common people. Indeed, it was precisely during this era that the ruling classes sought to demonstrate to the world their distance from the rest of society with their way of dressing, their bearing, their conversation, and even their eating and dining habits.

At the time, the consumption of certain foods, but especially the setting within which they were consumed, became a way to demonstrate the power of the lord or prince of the day . This power was no longer that of the Middle Ages, expressed through physical strength and skill in combat, but was now more refined, centered on diplomacy and the pomp of courts, but no less ruthless. Food was meant to be displayed, and the table became the stage for theatrically displaying opulence, decorum, etiquette, and, above all, distance from the meager tables of the majority of the population.

And just as in a theater, there was an impresario, the lord, an author, the head chef, and finally a director, the steward, the overseer of the princely and aristocratic kitchens, to whose creativity the table performance was entrusted. A performance in which no aspect had to be overlooked, from the decor of the room to the tablecloths, the table decorations called triumphs, from the serving dishes to the individual plates. Service was therefore an essential element of every banquet, a spectacle brought to life by highly professional performers, even endowed with a certain virtuosity. Thus, there were cupbearers, waiters, but also cupboard-handlers, capable of skillfully folding napkins into any desired shape, while the carvers could carve poultry in mid-air, holding the meat skewered on a large fork.

This tendency toward ostentation reached its peak on grand occasions, with themed banquets such as the one held for the wedding of the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso II d'Este, in 1565. The star of the feast was Neptune, and everything was arranged to make the guests feel like guests of the god of the sea himself. The setting was designed to make the table truly appear to be at the bottom of the sea; plates and serving trays were all crafted in the shape of shells, specifically for the occasion. The foods, from meats to desserts, were modeled after fish and sea monsters. The banquet was a triumph for the Duke of Ferrara and cemented the lord's power. Above all, it conveyed, along with many other banquets described in Renaissance chronicles, a splendid yet artificial image of the powerful figures of the 15th and 16th centuries, those who invested in theatricality to cement their power, which was too often illegitimate and usurped.

A theatricality that served to define a convivial space distinct, separate, and protected from the rest of the world, a space where social privilege and political power were dramatically contrasted with the world of hunger and poverty that existed outside the courts. In this sense, opulence, the desire for distinction, and the cult of refinement paved the way for the increasingly exclusive and increasingly phantasmagorical banquets of the nobility and sovereigns of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.