Sardinian autonomy & «differentiated» regions: the constitutional pact for the island is at risk

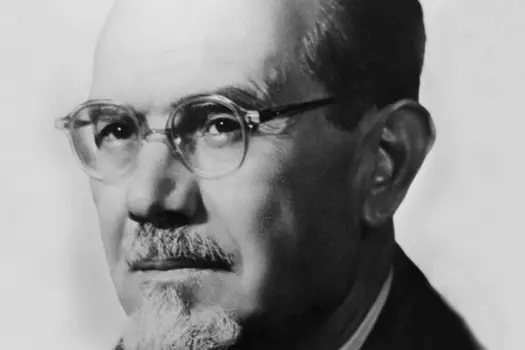

The bill proposed by the Minister for Regional Affairs is an unprecedented vulnerability for SardiniaEmilio Lussu

Per restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

His is one of the three signatures at the bottom of the Italian Constitution. Together with that of the President of the Republic, Enrico De Nicola, of the President of the Council, Alcide De Gasperi, that of Umberto Terracini, President of the Constituent Assembly, also appears in the Charter of Laws. It was he who presided over the Montecitorio assembly on 29 January 1948 when the island of Sardinia was transformed into an autonomous and special region. It was up to Terracini, shortly before fourteen, to give the floor to Luigi Einaudi, Minister of the Budget, the "black beast" of Sardinia. The one under discussion is the last paragraph of the statutory ordeal of the Region. It was Einaudi himself, the future President of the Republic, who formulated the key amendment of the entire structure of the constitutional "pact" between the State and Sardinia.

The final blow

A real final blow to be dealt without delay to the already feeble Sardinian Autonomy. Article 56 of the Statute is in the vote. In practice, the device which provided for the modification of the third Title of the Statute, to be clear the chapter of money and economic transfers to the newly created Region, with ordinary law "on a proposal from the Government or the Region". There are two additional amendments to be settled by a vote of the Constituent Assembly. The first was presented by the Minister himself. He asks that the ordinary laws, those that modify the resources destined for Sardinia, can be approved with a simple and harmless "after hearing the Region". The other amendment, on the other hand, is signed by Gaspare Ambrosini, from Favara, in Sicily, a Christian Democrat, constitutionalist, father of the division between Regions, Provinces and Municipalities. He is the speaker of the Sardinian Statute. The amendment proposal he presents is diametrically opposed to that of the Minister: the ordinary laws on financial resources - it is written in the amendment - can only be approved "in agreement with the Region".

«After hearing» the Region

Needless to say, as if Einaudi had placed a vote of confidence on that key passage, the Assembly approves the ministerial formulation of "after consulting the Region", practically nothing. Thus ends the "constituent" ordeal of the Sardinian Region. Emilio Lussu, the Captain of the "Sassari", knows that he has fully opposed the centralist and anti-autonomist thrusts of the state elite. His return to Sardinia, however, is bitter. He is aware that the newly approved Statute is an impressive constitutional recognition, but he perceives that the delays accrued, especially on the island, have deprived the Region of powers and resources to break "that spell of isolation of which the Sardinians are prisoners". An almost pro forma recognition that does not address, however, the indisputable reasons for the Autonomistic Specialty. It is no coincidence, in fact, that the first two Regions for which it was decided, right after the end of the Second World War, to recognize a specific and broad autonomy, powers and resources, had been Sicily and above all Sardinia. «Special regions because they are islands», argues Lussu, in that historic peroration for the invoked approval, joint and univocal, of the two statutes, the Sardinian and the Sicilian one.

Einaudi & Lussu

Already 75 years ago, however, the creeping annoyance of the State in recognizing the Island as those indispensable tools for recovering the economic and social gap linked to its double insularity, the one experienced towards the rest of the Continent and the one consumed with the isolation of immense portions of the Sardinian territory. The titanic clash between Einaudi and Captain Lussu in this constitutional affair struck at the very heart of the Sardinian question: recognizing Sardinia not only for the sacrifice of human lives paid for the state war, but also and above all for that "permanent" disadvantage of its insular condition. A decisive vulnerability in the relationship with the palaces of Rome which has perennially considered Sardinia a dependence of the State without ever posing the issue of a gap, yes, to be measured and compensated. In this "Special" story, the Sardinian Region has found itself perennially opposed by the State not only on economic grounds, but also on the level of competences and powers. A specialty of constitutional rank, which however remains unfinished from every point of view, violating in substance itself that "constituent" pact of '48.

The Northern Assault

Today, 75 years after that approval, the wound of that unfinished constitutional law is reopening. The advent of the new government has without delay brought back the question of "differentiated autonomies", to be more explicit, the request of Veneto, Lombardy and Emilia Romagna to obtain more powers, more competences and above all more money from Rome. The issue is not whether or not to agree to the granting of greater autonomy to the strong, indeed very strong regions of the North, the question is higher and with far more significant implications than a mere transfer of skills and resources. At stake is what the jurists of the Charter of Laws define as a real threat to the Constituent Pact. It is here that the statutory conquest wrested by Lussu and the constituents in '48, albeit limited and incomplete, today acquires the absolute value of the "special" constitutional prerogatives reserved for Sardinia. In practice, the fact that the Italian Constitution envisages two levels of regions, the special and ordinary ones, places an absolute constraint that cannot be modified except with a constitutional reform. A hierarchy of powers, resources and competences which places the regions with special statutes in a step, at least constitutionally, higher than the ordinary regions. Of course, now Article 116 of the Constitution provides for new forms of "differentiated" autonomy for the ordinary Regions that may claim them. A possibility, however, which cannot and must not in any way infringe that graduality sanctioned at the constitutional level. The text of the bill prepared by the Minister for Regional Affairs and Autonomies, the Northern League supporter Roberto Calderoli, belongs more to a war arsenal than to the good grace of the institutions. Regardless of all consequences, canceling bon ton and courtesy, the draft distributed with both hands by the Northern League minister, as if it were a hunting trophy, breaks with the grace of a tank in the already tenuous balance between powers and responsibilities envisaged by the Italian constitutional framework .

Sardinian cards

The sneaky attempt that creeps into the palaces of Rome and beyond to pass off the Regions with Special Statutes as out of time, as romantic concessions of a bygone era, collides with the strong, clear and unchangeable assumptions of the Sardinian specialty. Like it or not, Sardinia is the only Special Region that can count on all three conditions of its recognized autonomy: it is a distant island, has a very low population density and is inhabited by a community "of speakers of a minority language ”. All elements that have not changed in 75 years of autonomy. Isola was, Isola remained very distant, very low population density was and remains, a minority language before and now. One fact is certain, that unfinished Specialty not only hasn't completed its task, but right now it becomes an essential element to reopen the close confrontation with the State, starting from a measurable and non-mitigatable fact, its insularity. It is all too clear that the Calderoli proposal, to be pursued through an ordinary law, has a direct and indirect impact on the entire constitutional system. The risk is that the three regions of the North will acquire, with an ordinary law, more powers, more competences and above all more resources than the Regions considered "Special" by the Constitution. The reasoning is simple: if the ordinary "differentiated" regions of the North took ten steps forward, the special regions, Sardinia above all, would remain even further behind, breaking the constitutional principle which theoretically recognized them more powers and resources for a permanent rebalancing of structural and infrastructural gaps. For the island this is the last call to forcefully pose, at the cost of appeals before the Constitutional Court, the definitive question of the implementation of the island's rebalancing, desired first by the Constituents, then by a fiscal federal law, the n. 42 of 2009, and by a constitutional principle just passed by the Parliament. The game, therefore, is high. At stake are the values of Autonomy, the right of Sardinians and Sardinians to fair treatment, on a par with any Italian and European citizen, without further discrimination.

(3.continue)