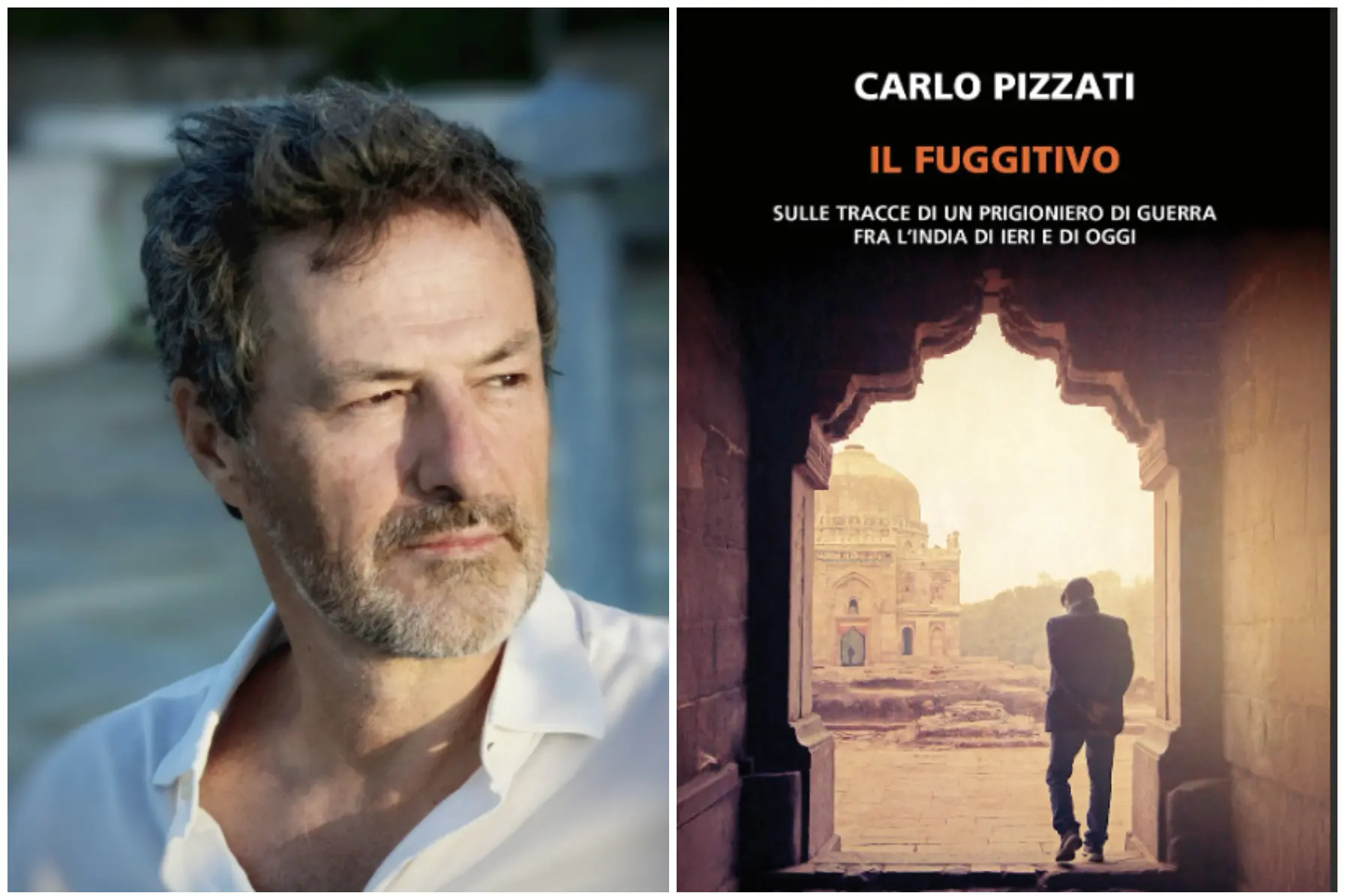

"The Fugitive": Carlo Pizzati on the Trail of a Prisoner of War

Following the trail of a prisoner of warPer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

In December 1940, a young Alpine officer, Ottone Menato, was captured in Egypt by the British. After an adventurous escape, he was arrested again in Yemen and transferred to British prison camps in India. But Ottone refused to give up: he escaped the fences of Bangalore with three comrades. Hunted in the jungle infested with panthers, snakes, and other wild animals, he was aided by Indian shepherds and farmers. Recaptured, this time he was interned on the slopes of the Himalayas, where he discovered an unexpected microcosm: theaters with actors performing in women's clothing, open-air cinema, cultural debates, and a community that, after September 8, 1943, split between anti-fascists, with greater freedom of movement, and the so-called Fascist Republic of the Himalayas, the non-collaborators held in Camp 25.

Eighty years later, Carlo Pizzati , Ottone's descendant and a writer who has lived in India for fifteen years, sets out on his great-uncle's trail. Thus was born Il fuggitivo (Neri Pozza, 2025, €21.00, 320 pages. Also available as an ebook) , a novel-reportage in which, between Mumbai, Bangalore, and Dharamsala, amidst secret archives and reconstructions of British intelligence's plans to "re-educate" Italian prisoners, an intimate dialogue with the past emerges, intertwining the India of today, projected toward an increasingly powerful future, with that of the 1940s, poised between colonialism and independence.

We first asked Carlo Pizzati how the idea of reviving the Ottone Menato story from oblivion came about.

I had already been living in India for five years when I reread Latin Lovers, the novel my great-uncle Ottone Menato had published in 1968 about his six years of captivity in Egypt, Bangalore, and Dharamsala during World War II. Suddenly, I realized that my idea of India had also been formed in those pages. Ottone, the heroic lieutenant of the Alpine troops who was a poet, journalist, and writer, appeared to me as charismatic and brilliant as I remembered him. He spoke to me through the character of his alter ego in that novel, Diego Taranto. And he had a lot to tell me. I listened. From this dialogue with the ghost, retracing the steps of Latin Lovers in today's India, Il fuggitivo was born.

Which India did Otto encounter during his odyssey?

“Imagine Ottone and his companions crossing the forests north of Bangalore, hunted by military police. Snakes in the foliage of the fugitives' beds, two panthers emerging from the bushes. And then the betrayal: the fake friends arriving with the gendarmes. But also a rich farmer hosting a banquet in his palace in honor of the fugitives. In the private archives of the Oral History Museum in Bangalore, I found testimonies of elders who, as children, would march 10 kilometers just to see the imprisoned soccer players, including Uncle Ottone, at the Sunday match against the British. Many Indians cheered for Italy, even chanting for Hitler. Why? Because of the ancient rule that the enemies of their enemies, the British who occupied their land, became friends.”

How did Otto deal with a country so far from his own?

In his elegantly handwritten diaries, enriched with period clippings, I found a man hungry for understanding, a scholar who wanted to understand India's geography, history, and above all its religions. There was love for that country, even though the jailers who killed some of his companions were Indian. Ottone studied the sacred texts, which transformed him. Upon his repatriation, he practiced yoga for years, anticipating the hippie trend of the 1960s. Nearly seventy years after him, I arrived in India to study yoga, meditation, and decipher Ayurvedic medicine. But I was also inspired by Ottone, as I realized while writing The Fugitive.

What remains of the India of over eighty years ago today?

In the same areas where Otto fled, I found ancient temples next to stalls where you can buy coconuts with the tap of a smartphone, in India's Silicon Valley of Bangalore. Today, it's a sprawling city teeming with warehouses. India's millennia-old history is made up of sudden bursts of energy and long pauses, shrouded in tradition and a religiosity that survives with intense devotion. Consequently, a sacred relationship with the guest remains, a certain gentleness, often misinterpreted by Europeans as surrender, a strong patience, mistaken for resignation.

Where is India going?

"In 15 years, I've seen India economically surpass Italy and other self-proclaimed developed countries. New highways, airports, skyscrapers, industrial ferment. But the real miracle is that it still retains the patient strength that Ottone glimpsed 80 years ago. If it could dismantle monopolies and distribute this wealth more effectively, India would be truly unstoppable."