Lorenzo, the bricklayer who saved Primo Levi

The Piedmontese historian Carlo Greppi reconstructs the story of the man who lived outside the Auschwitz fencePer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

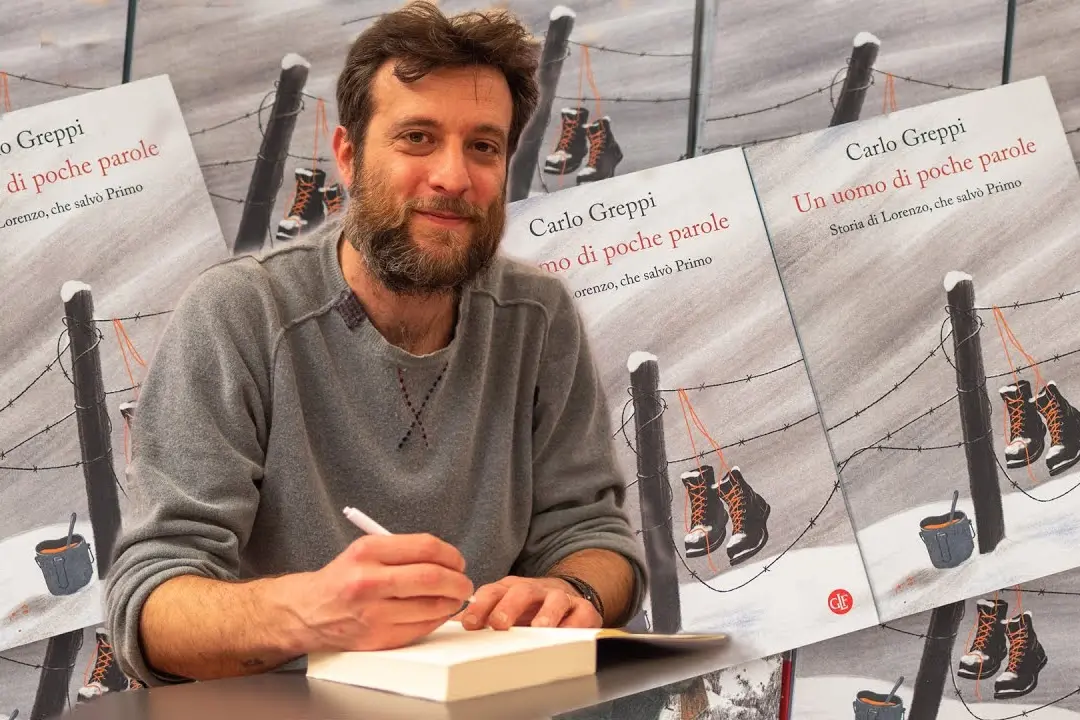

The starting point are a few words written by Primo Levi in "If this is a man": "I believe that I owe it to Lorenzo that I am alive today...". Yes, but who was Lorenzo? Why was he so important to Levi and yet is he practically unknown? The answer to these questions can be found in the latest book by Carlo Greppi "A man of few words" (Laterza, 2023, Euro 19, pp. 328. Also Ebook) in which the Piedmontese historian with scrupulous historical research "resuscitates" from oblivion of time Lorenzo Perrone.

He was a Piedmontese bricklayer who lived outside the Auschwitz III-Monowitz fence. A poor man, with a difficult and almost illiterate character who every day, for six months, brought Levi a tin of soup which helped him compensate for the malnutrition in the camp. But he didn't limit himself to assisting him in his most concrete needs: he went much further, risking his life also to allow him to communicate with his family. He took care of his young friend as only a father could have done, responding firmly to every attempt by his friend to keep him away from him and from the dangers he could run by helping a Jew locked up in a concentration camp. "I don't care at all" Lorenzo simply replied and continued to get busy.

The result was an extraordinary friendship which, germinated in hell, survived the war and continued in Italy until the poignant death of Lorenzo in 1952, bent by alcohol and tuberculosis. Primo never forgot him: he often spoke of him and called his children Lisa Lorenza and Renzo, in honor of his friend. But beyond the biographical and historical data who Lorenzo Perrone was, we ask Carlo Greppi directly: «He was the human embodiment of good. Nothing less, nothing more. He wasn't a hero or a supernatural being. He was an imperfect being like all of us, but after getting to know him I understood how right Primo Levi was when in If this is a man he wrote: 'But Lorenzo was a man; his humanity was pure and unsullied, he was outside this world of denial. Thanks to Lorenzo, I have never forgotten that I myself am a man'».

Although he was not locked up like Levi in Auschwitz III-Monowitz, Lorenzo Perrone was unable to find a normal life once the war was over…

«He returned home literally shredded by what he had seen. Although he had been decisive for Levi's survival, and not only that, the experience in contact with the reality of the concentration camps made him lose his compass. It was as if his life had found meaning in the help he gave to the unfortunate prisoners in the concentration camp, but that this meaning had been lost once peace returned. After Auschwitz Lorenzo met an inexorable sinking that led to his death in a few years".

Who has preserved the memory of Lorenzo Perrone?

«The family has kept his memory reluctantly, in intimacy with only a few sporadic interviews in the 1990s. Lorenzo then had in his town, Fossano, some singers who have handed down his memory, such as Don Carlo Lenta and the mayor Giuseppe Manfredi. Not so much if we think of the importance Lorenzo Perrone had in Primo Levi's life and therefore in our history. What would our perception of the Shoah have been like if Levi hadn't survived the concentration camp and hadn't left us his testimonies?».

In your books you often prefer not to focus on the great characters, but to study what you call the "rubbish stones" of history, ordinary, ordinary people. Why this choice?

“Because history is made up of highs and lows. It is an interweaving of history with a capital 'S' made up of politics, battles, characters and the ordinary history of ordinary people. These are two aspects that interpenetrate and that both must be kept in mind. My book is the biography of what appears to be a 'waste stone' of history, of one of those people who apparently live without leaving a trace or memory of themselves. But, on closer inspection, many of them are the true 'corner head' of humanity».