Living in times of “bad faith”

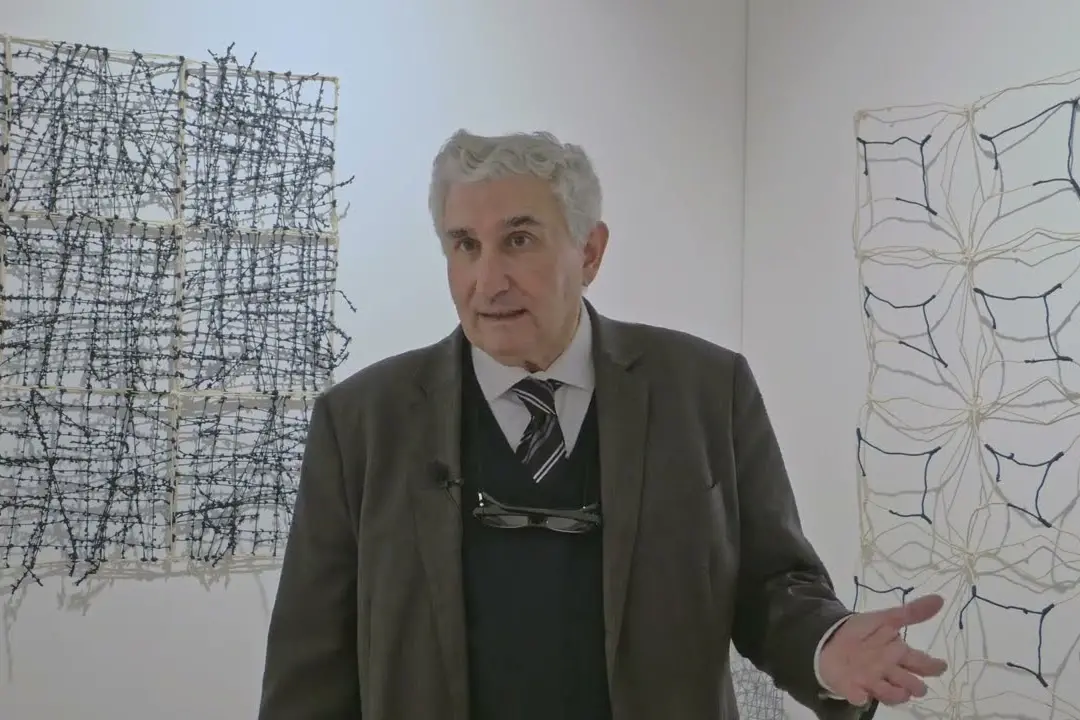

Michele Camerota, of the University of Cagliari, reconstructs the Hamlet-like choices of Giorgio de Santillana during the twenty years of fascismPer restare aggiornato entra nel nostro canale Whatsapp

Giorgio de Santillana (1902-1974) is not very well known to the general public today. He is, however, one of the many Italians who during the twenty years of fascism left our country to seek his fortune in the United States . In this country he taught at MIT in Boston and became an authority on the history of science , so much so that his books, such as “Hamlet's Mill. Essay on myth and the structure of time” (1969) are today considered classics of the history of thought.

Before becoming a famous intellectual and academic, however, De Santillana was a talented young intellectual trying to emerge in Mussolini's Italy . Those were years in which the distinction between good and evil, between opposition to the fascist regime, indifference and tacit consent was often subtle. It was an ambiguous distinction, "Hamletic" just as Giorgio de Santillana's attitude was ambiguous and "Hamletic". An ambiguity that weighed heavily when in 1936 as a young historian of science he left Italy to seek academic fortune and economic security in America. Friend of many anti-fascists, however, the moral conscience of the fight against fascism outside Italy came into the sights of Gaetano Salvemini, who privately warned his friends not to trust de Santillana. But then was this illustrious thinker so celebrated today in the United States and Europe an opponent of fascism, a supporter of the regime or, even worse, a spy infiltrated among the Italian exiles?

Michele Camerota , professor of History of sciences and techniques at the University of Cagliari, started from these questions in his essay entitled “Hamlet's ghost. Giorgio Santillana between Salvemini and Mussolini” (Hoepli Editore, 2024, pp. 208, also e-book). The result of extensive research in public and private, Italian and American archives, the volume does not aim to condemn or absolve a man who lived, like many of his generation, in difficult times. Rather, it reconstructs a case of conscience, highlighting how the twenty years of fascism often forced intellectuals and not only them into opacity, to live in a daily condition of bad faith, to use Guido Piovene's famous definition. This great writer and journalist defined bad faith with illuminating clarity as "a conscious and unconscious lie". And again as «an art of not knowing oneself, or rather of regulating the knowledge of ourselves according to the yardstick of convenience». In short, bad faith was not so much courtliness, but a distorted faith or trust, ambiguous and tainted by doubt and therefore Hamlet-like, which led you to acquiesce to power even if that power was not part of you.

Santillana was, like many Italians of his time, engaged in a restless wavering between opposing political tendencies , which led him to appreciate anti-fascism and anti-fascists and at the same time not being able to avoid adhesions with Mussolini . Symbol of this uncertain fluctuation of the young Santillana is the inability to express a clear detachment from the Duce and the complicated relationship with Gaetano Salvemini, whose consent Santillana sought, receiving for a long time only a cold and suspicious detachment. However, in 1945, once the war was over, the relationship between Salvemini and Santillana was excellent. What had happened in those years? Camerota collects the clues at our disposal, offers the study of unpublished documents and, as in any self-respecting detective story, offers us a possible solution.